What to Do When the Words No Longer Fit

Creative possibilities for language that you’ve outgrown, is outdated, or outright cringeworthy.

I don’t know about you, but I have stacks of old journals, and in the spirit of Taylor Swift, the eras have evolved. While the thoughts and takes are true to me then, sometimes (many times?) they are wildly afield from my voice and vision today. Uncomfortable as this may be, I’m convinced this is as it should be, as it speaks to personal growth.

However, that’s a lot of ink to have outgrown, and if we believe as writers that there’s no wasted page, what is it all for?

This tension is exactly what sparked me to

’s concept of upcycling words that no longer fit, which she was kind enough to break down in this guest essay today. I love the creative, compassionate practice she introduces here, and hope you do, too. You can subscribe to Cara’s newsletter “Coloring Outside the Lines, Again” here.P.S. In our last letter, I asked about your interest level in more personal essays in this space, and heard a resounding yes! Thank you for your input, and accordingly, I’ve got some in the works.

Upcycling Words that No Longer Fit

By:

“It’s just so hard when it sometimes feels like everything needs to be upcycled at some point,” my friend Marla said.

We were brainstorming our next writing workshop to lead together, and having a hard time narrowing down our topics. And that’s when it hit us: sometimes we have to upcycle words that no longer fit.

We knew we were on to something. Although I can only speak for myself, this much I know: as a writer, writing starts with noticing. I think of Mark Twain, who was often called a natural noticer of the world around him — that’s why, when you read a classic of his, like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer or (my personal favorite), A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, you feel like you’re brought back in time to people and a place entirely not your own.

But what are we to do when the people and the place, the belief systems and the words we used to use within those belief systems no longer fit who we have become? As we grow and change, we might read words written 10, 20, 30 years ago — words, in fact, that would never come out of our mouths now, words that feel utterly cringeworthy to our ever-evolving human selves. When we outgrow old language, is there really no other option than to take it out with the trash?

Through the practice of upcycling language we’ve outgrown, we can lean into the words inside us; we take out paper and pen and begin to write our way through an old and archaic lexicon.

In the creative process of upcycling, we can then freely wrestle—flipping words upside-down and turning them inside-out. We can rearrange phrases and cross out entire sentences; we can let our fingers and our brains and our intuitive, honorable hearts do the work of revisiting and rearranging to turn stale thinking into something new and healing.

Because when all is said and done (if a piece of writing can ever be said and done), healing often does begin to have its way inside us, maybe because we've made room for the many versions of our messy, human selves.

When we upcycle words that no longer fit, we find new ways forward.

We find that we are our past and present selves—we find, always, that both can be true to a certain extent.

How, then, might a writing exercise like this happen?

Without giving away the whole workshop, let me guide you through one of my favorite ways to upcycle words: blackout poetry!

Blackout poetry is “a process of narrowing down the words you don't want, then selecting and arranging the words that are left.” Blackout poetry typically originates from someone else’s words, though you can try it on your own words that no longer fit as well.

It can be as easy as taking Sharpie to paper, traditional rules are as follows.

Identify your source material

Your source material can be something you vehemently disagree with or something that just doesn’t sit right with you. It can be an old blog post or journal entry; a poem you wrote 20 years ago or a sermon you preached before a theological shift; it can be hate mail you’ve received or a tweet that made you cringe. Really, the source can be whatever you need and want it to be.

Once you’ve identified and printed out your source, read over it a couple of times. Whether I’m doing this alone or with a group of people, I like to read it out loud at least once; speaking and hearing the words out loud often changes it.

Take, for example, a couple of mean-spirited tweets I once received. When I left the traditional workforce more than a decade ago to pursue writing and speaking full-time, I was pretty desperate for publication.

So, I wrote an article about being a newcomer to a church, offering readers several different things churches could do to welcome visitors. My own beliefs are different now: I would not write that same article today, nor would I write for this particular publisher today. But because the publisher owns the rights to an article I was paid a whopping $35 to write, they continue to republish this article once or twice a year.

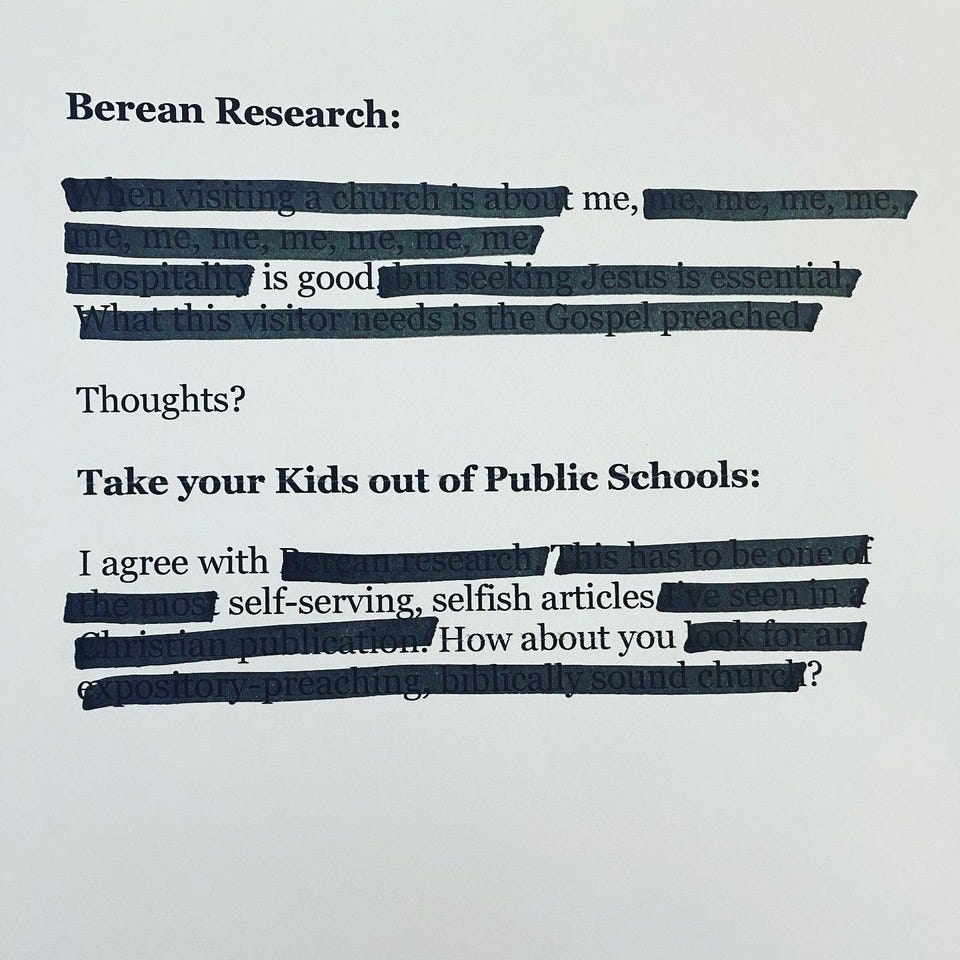

Which means that I continue to get a slew of unsolicited comments from strangers—with even stranger digital handles—on the Internet, like this:

Notice and annotate what calls for your attention

Now that you’ve read it out loud, notice what sticks out to you. Underline or draw boxes around words that stand out to you. In my example, I drew boxes around the following words and phrases: me, is good, I agree with, etc.

Find connections

After you’re done with the second part of the exercise, look for any connections exist between the highlighted words.

What do the words or phrases have in common? Do they speak of goodness or anger, do they emanate sadness, grief or loss? Are they filled with hope, or perhaps with change? Sometimes you find a theme; sometimes you don’t. Sometimes, in blackout poetry, you purposefully look for a theme; sometimes you skip this step altogether.

Color it in

Finally, color in or black out the words in between all of your underlined or boxed areas, creating a new pathway through an old work, and new meaning with it.

Congratulations! You have now officially created blackout poetry!

Perhaps, upon reading it over again, you find that you need to blackout a tad more. Maybe you find that it’s perfect as is—after all, it’s done its job of helping you move the needle forward a tiny bit when it comes to healing and creating new paths forward.

Here’s how mine ended up:

For me, the poems I created aren’t necessarily going to win any poetry contests, but they certainly served to flip the narrative on its head.

Whether your blackout poetry creates a new narrative from old thinking, or makes something beautiful out of the negative words of others, this practice can become a source of empowerment. After all, “Me is good.”

I hope upcycling your words will do the same for you.

is a writer, speaker, and nonprofit communications consultant, passionate about issues of justice, race, and spirituality. A former high school English and leadership teacher turned nonprofit executive director, she holds a master's of theology (Fuller Seminary) and is author of The Color of Life. She lives with her husband and two elementary-aged sons in Oakland, CA.

This is awesome! And I really appreciate this look at Cara and Marla's upcycling process. Marla Taviano is also a friend of mine and I am currently writing a musical based on her book unbelieve: poems on the journey to becoming a heretic.

"I agree with self-serving selfish articles." How about you? 😅

Too funny

Great article

Love the method