Stetting the Tears: Writing About Pain

How writing lifts up a writer’s inherent agency of choice and voice

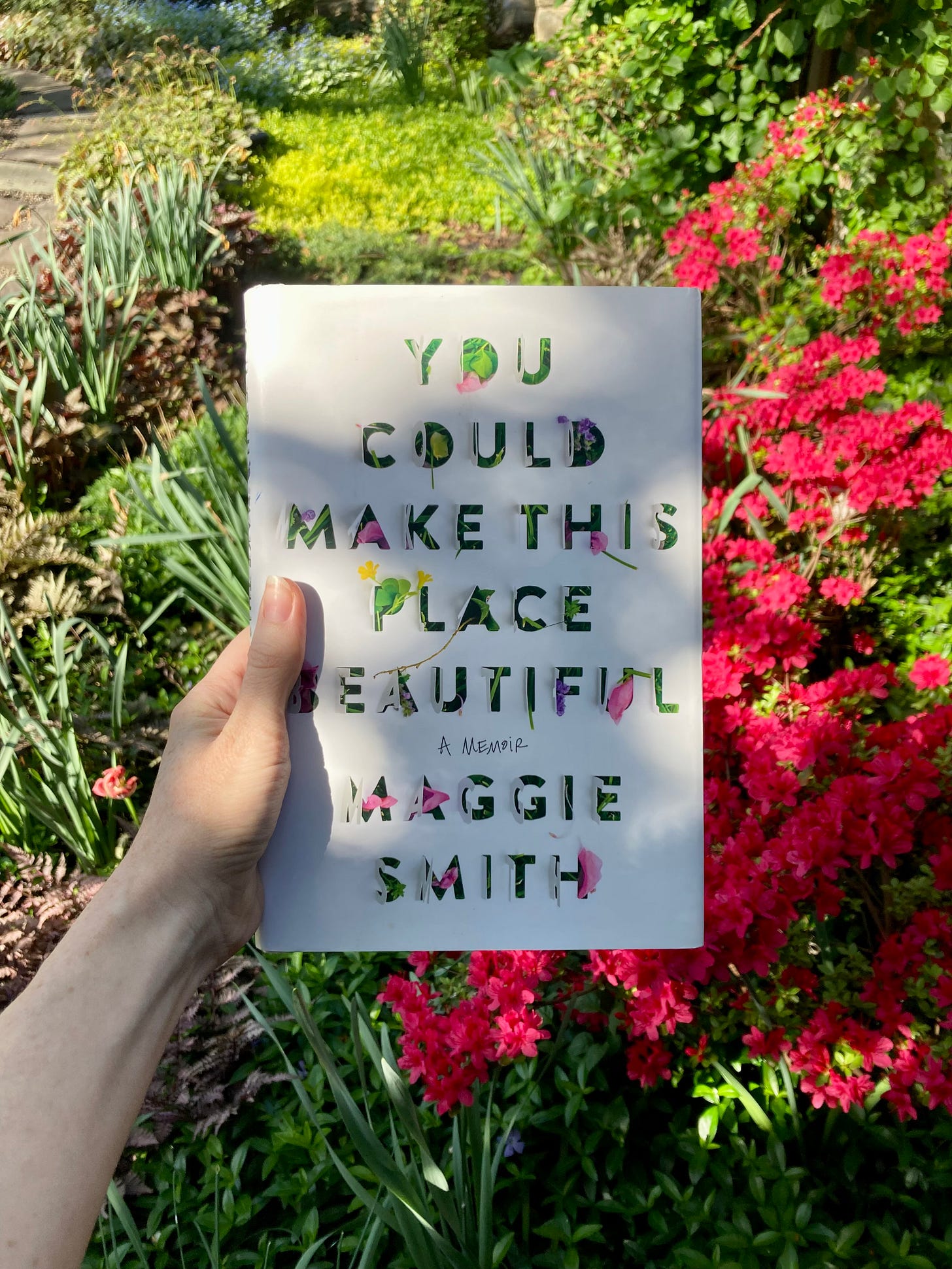

Welcome to Slant Letter’s spring seasonal intensive! Become a paid subscriber to join our close reading of Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful for an editor’s annotated insights on an extraordinary memoir that all writers can learn from. Here’s what we’ve covered so far and what’s next. Join us!

1. The Art of the Caveat

2 . Details that Tell, Details that Move

3. Writing about Writing: The Thrills and the Trade-offs

4. Metaphor: What Makes It Work

5. Wordplay (and Its Secret Talent!)

6. “Stetting the Tears”: Writing About Pain

7. “The Flickering Is Yours”: Final Thoughts

Behind every written work is a backstory, and You Could Make This Place Beautiful tells a wild one.

In an essay titled “The Edits,” Maggie Smith writes of her experience pitching her Modern Love column, and running it by her ex-husband as a courtesy. What came back was a demand to pull to piece altogether and, when she declined, a slew of requested edits, including a strike of her tears in the piece. She writes,

“The man I’d befriended in a writing workshop tried to delete my grief on the page.”

What I notice in this essay and what I love: how Smith calls upon the writing process as a metaphor to interrogate the art of a life, how she uses the editorial process to lift up the inherent agency of choice and voice.

The narrative is multi-layered, a bold blend of on-the-page and off: her ex tries to stop her from voicing her experience. She refuses, then publishes this backstory here in the sacrament of print. She doesn’t need to color in commentary because his behavior speaks for itself:

“His edits…were more psychologically revealing than almost anything he said in couples counseling or to me privately.”

Tears mean someone is in pain, and pain means someone is responsible, and omitting the tears means that someone does not want to be.

You can tell a lot about a person by what they want redacted. You can tell a lot about a person by what details they want omitted. You can tell a lot about a person by what narrative they insist on, and just how far that narrative frays from reality.

How she lands the essay:

“I spent more in legal fees defending my right to publish that essay than I was paid for that essay. And the tears? I stetted the tears.”

“Stet” is a Latin word meaning "let it stand," and it’s used most commonly by writers in the copyediting or proofreading process to essentially strike an edit, or revert to the original text.

You can tell a lot about a writer by what honest emotions they let stand.

Her ex was asking her to change the narrative. Not just what happened, but the emotional response to what happened. But no one can take that from you. The happening will always be outside our control. But the becoming, in response, is yours and yours alone.

Writing, in this way, can become a powerful personal practice of reclamation as you sound your voice, name the truth of your experience, and make the bold choice of letting it all stand. What a profound way to return agency to anyone who feels their agency has been wearied and weathered due to circumstances outside their control.

As Smith says, personal narrative is a “tell-mine.” The tears are yours, as is the telling. Writing is animated by self-expression, and this cannot be outsourced. No one can tell you what you experienced, though some will try. Like Smith, your self-expression is a right you may have to fight for, but only you can speak to what your experience was like.

This is why, when it comes to writing our pain, I feel strongly that you write the first draft for yourself first. Writing is a space where you deserve to be safe to say what needs to be said, uninhibited by self-censoring tendencies or stet battles.

Here, I might gently reframe the “shitty first draft” as a processing draft. It’s supposed to be scrappy. It’s unpolished on purpose—because the purpose is to let it all stand. You can’t sort through an experience and its prism of emotions until you’ve first gotten it all off your chest and onto the page. More to a point, any draft that skips the personal processing becomes a mere performance piece—it might be styled on the surface, but it lacks the depth and dimension that emotional honesty inevitably invokes.

So give yourself the gift of the processing draft, and let it all stand. Strike nothing. Stet everything. See what you discover, and discover all the ways you might be surprised when you allow yourself to write without filters.

The truth is you can stamp the scary bits down, or you can let them stand. You can suppress the emotion, or show up to it and give it a fair hearing. Make no mistake: the difference will show up in your writing. You can tell when a writer is squashing it down, because they’ll downplay, dismiss, and deflect. And I think you can tell when a writer is showing up to pain and tending to it, because that’s most often when, as readers, we recognize ourselves and quietly say, “Me too.”

When we let our emotions stand, we let them live. We acknowledge them as among the living: firing in our synapses, catching in our throat, quickening in our pulse. If you squash all that down, how are you supposed to keep moving (another Maggie Smith-ism)?

That’s the power of words: they always take you somewhere. Ultimately, writing is a practice for moving through. Your processing draft can be your space to take honest inventory of the tears along with the good times, the banner days and the burn-it-all-down days—not to get stuck there, but to courageously engage the process of catharsis. To unburden your life by leaving your pain on the page so that you might live it more freely. And you deserve to live free.

💬 I’d love to hear from you: what challenges have you faced in writing about your own painful experiences? What are some ways you have “stet the tears” in your own work? Tell me your victories!

Take heart and stay feisty,

P.S. Did you see

’s new book announcement? It quite literally has your and my name on it. Preordered and can’t wait!If you’ve found something that speaks to you here

Hit that 🤍 button, restack this, or forward to a friend. This letter is this editor's off-hours labor of love. Your word of recommendation is how our kindred community grows.

Oh man. You and Maggie Smith and my book coach have staged the best sort of intervention for my own writing. I'm constantly having to relearn the beauty of the processing draft, but framing it as an opportunity to liberate my stolen agency--yes. Thank you all!

This is so good. I’ll often end up cutting the first two pages of writing for a post, before I realize I got to the heart of what is going to resonate with other people. But I always have to write the whole thing — the swear words, the whining, all of it — to get to anything that is honest enough to really be helpful.

When I was in the worst of counseling I’d write and write and write. I always felt like it was completely over emotional and must be such an exaggeration, but then I’d go back and read it later to find that — minus the swearing — it would usually just be me telling the truth without hedging. It’s so interesting how much we think we say the thing plainly, and how much we often don’t.