Welcome to Slant Letter’s spring seasonal intensive! Today’s letter is free for all subscribers, but become a paid subscriber to join our full close reading of Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful for an editor’s annotated insights on an extraordinary memoir that all writers can learn from. These will be exclusive letters sent straight to you running from April through May. Join us!

“I like to hear the sound of form, and I like to hear the sound of it breaking.” -Frederick Seidel

More than anything, this is the sound I hear as I read

’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. Here is a poet who knows the rulebook inside and out when it comes to form, who takes all that knowledge to the memoir genre and then shuffles the whole deck, making rules of her own.As I’ve said before, the rule I feel fustiest about is that you have to master the basics before you earn the right to break them. The brilliance of this book is that Smith does, and what follows is the sound of things breaking—a sound she makes beautiful.

One of my personal editorial rules is that there needs to be a very good reason for a writer to write about their writing process in their book. Naturally, I’m all for digging deep into the writing process! But I find craft conversations to be most compelling as a parallel piece to the work, not as asides within the work itself. They make for an excellent conversation to have around the book, but independent of the text itself.

I generally caution writers against writing about writing within the book because it renders the book self-aware to the point of distraction. Writing about writing breaks the fourth wall and reminds the reader that the work is a production. It pulls back the curtain to reveal the puppet strings and stage lights, while I tend to think readers want to suspend disbelief and get swept up in the full experience of the show. They want their senses to be engaged, they want the emotional stakes of the story to be real to them, and I don’t think they want this immersive reading experience to be interrupted by technical notes.

Of course, a book is a production! This is no statement whatsoever against the integrity of the work. It takes unbelievable work—honest work—to craft a story that speaks to readers. But showing too much behind-the-scenes holds the potential to distract and detract from experiencing the story in its real-time glory. It would be like trying to watch a film drama and the director keeps pausing to explain to you how they sourced the costumes and why they chose this camera lens, this angle. It pulls you out of the moment, when, on the whole, I think readers want to be present to the real-time narrative.

Making the writing self-aware can be done, but these are the risks, even as there are always stylistic exceptions. And that’s why I was so fascinated by this read in which an author not only writes about writing, but makes the meta the very spinal structure of her entire book.

For example:

Chapter titles include direct address to readers, such as, “A Note on Plot,” “A Note on Character,” and “Full Disclosure,” which details how the author’s advance money kept her and her children from losing their house during the divorce proceedings.

The author self-redacts, “

Sad-AssDivorce Dream,” as if editing in real-time (208).She interrogates the classic hero’s journey of rising and falling action followed by resolution even as she fights to make some meaning out of her own journey.

She openly wrestles with how hard the writing process can be:

“Sometimes it feels like each poem I write is a draft of The Poem I’m trying to write—that singular, golden, impossibly definitive poem. The one poem I’m trying to live. Or the one life I’m trying to write. The mine” (170).

One chapter examines how the title holds up its promise to its readers, and at one of the most direct points, asks outright, “How’s that for meta?” (239).

If any of my authors had outlined any of this in their proposal, I would have most assuredly advised against it. Candidly, I cringe to think if any writer might have tried such tactics as a stunt or without the meticulous study of style before attempting to make a stylistic exception. But that’s not what I find here. It’s for you to decide if you think the meta treatment “works” or not, but I think it does.

Here are some theories about why it works:

Form is meant to serve substance, not the other way around.

I read this book as a deconstruction of form itself, in the aftermath of a deconstructed marriage and shape of family life. It’s about processing that which can never fully make sense: what went wrong, and when? And most urgently, Why? “Every book begins with an unanswerable question,” Smith writes. Why is always the unanswerable.

So the subversive play with form is appropriate to the substance of the work. Smith shows us that searching and understanding life’s events can be its own creative process. Through revealing her own process, she shows us that we are allowed to reframe, to tell ours, to self-edit in real-time with the wisdom of the retrospect.

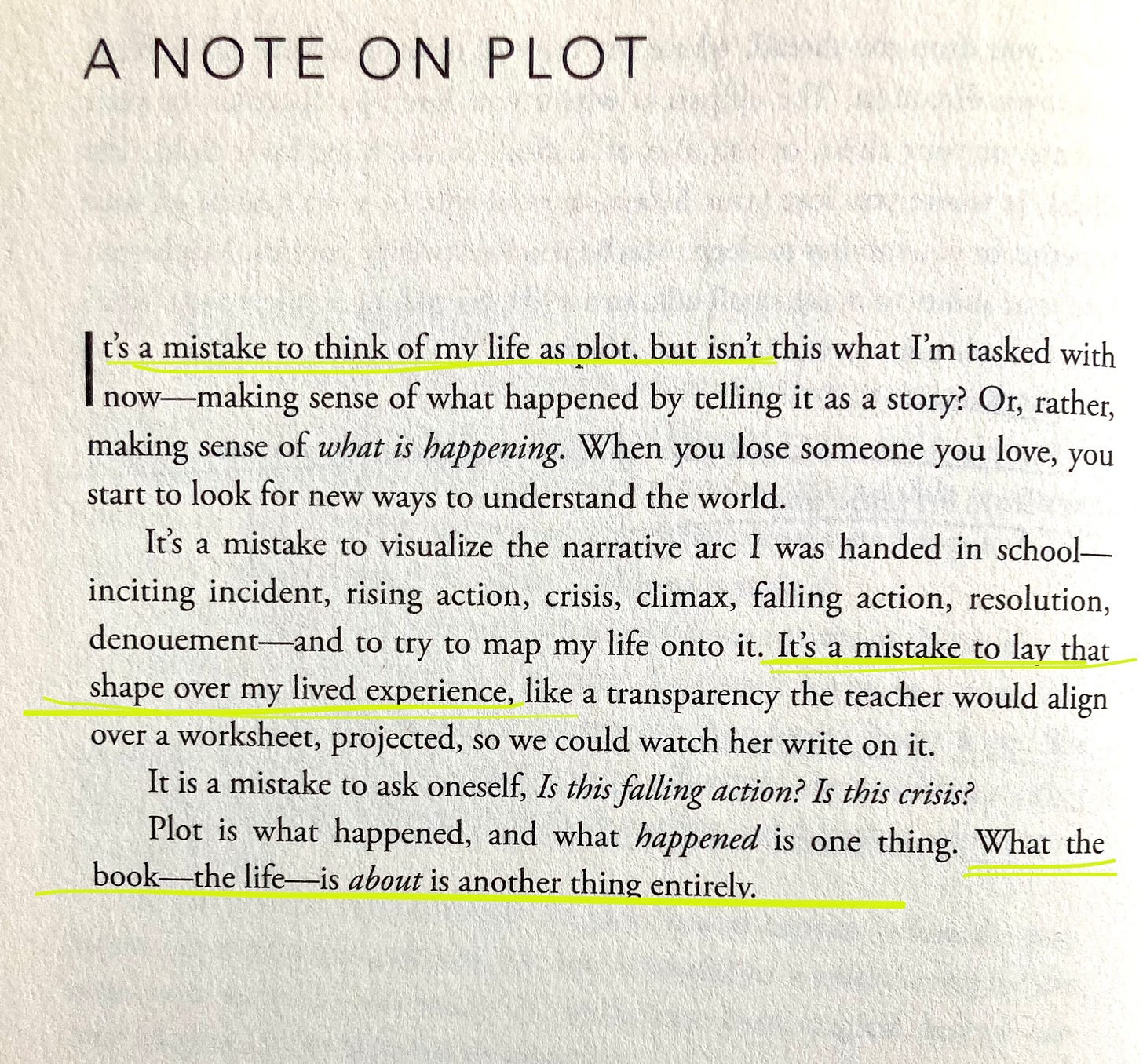

The form deconstructs the classic hero’s journey with all its lauding of the linear, to ask if this is really the shape all of our stories take. “It’s a mistake,” she says, to expect life to take such clean narrative shape:

Then she offers another frame, another form, for narrative meaning-making. The cento, Smith writes, is “a kind of poem assembled using the lines of other poets. Memory, too, is assemblage—a kind of cento, collaged from pieces. From the scraps of a life” (286).

I like this proposal: not a linear rising and falling and resolving, but a heart-forward foraging, hunting and gathering, sorting through the scraps toward a fuller view. Something we can call mine.

I have plenty of bones to pick with the hero’s journey. Here’s one of them: the plot leans too heavily on the external action of uncontrollable circumstances. The cento, by contrast, is work that can only be done in the realm of the interior life. If the plot is “what happens,” the cento might an art form of the chosen response. In the end, I find this vision far stronger: not a right line rising to the right (or you’re doing it wrong), but making peace with broken pieces, fashioning them into something we can rightly call beautiful.

It helps when you’re a public figure.

Smith’s work has an international profile and she calls upon some of her public professional life already familiar to many to show there is more to the story, as there always is. You can cite your own trade-offs for living such a public life, for better and for worse, but it helps that her narrative is known on some level before offering the “more.” The orientation points are already there. Conversely, it can certainly be harder for writers who are not publicly known to generate interest in their own story behind the story, just to name one of the difficult realities of publishing.

Breaking the fourth wall becomes a way of leveling with her reader.

By pulling back the curtain so fully, Smith is showing us that this—the final published work—is not a performance piece but the candid picture of a life in process. Again, form serves substance here. The form underscores the point: By giving us such a deep behind-the-scenes view, she shows us that there is always more to the story than any surface-value “scene.”

Smith does not present herself as a sage, but a life in process, wrangling with the unanswerable on the page. Her notes on process put this work out in the open, releasing her from the burden of presenting a too-clean, forced-bloom brand of resolution that overpromises. From my seat in nonfiction publishing, I find this a balm. She even goes so far as to assign some of the interpretive work to her readers: “I’m handing you a stack of Polaroids to shuffle in your hands, so some of the work is yours” (170). Bold! I like it.

In a chapter titled, “How It Ends,” she cites the poet Stanley Plumly who told her that poems “begin in the middle and they end in the middle, only later” (306). How like life. There’s no greater way to earn your reader’s trust than by leveling with them.

I’d love to hear from your in the comments! Do you enjoy reading a writer’s take about writing within the work, or do you find it distracting? Do you do it yourself? How did you read Smith’s take on this?

Editor’s note: This is a free post to show you what we’re doing here in our spring seasonal intensive. Next week we’ll continue our series for paid subscribers with our study of what makes metaphor work, following our full line-up:

1. The Art of the Caveat

2 . Details that Tell, Details that Move

3. Writing about Writing: The Thrills and the Trade-offs

4. Metaphor: What Makes It Work

5. The Power of Wordplay: A Case Study

6. “Stetting the Tears”: Writing About Pain

7. “The Flickering Is Yours”: Final Thoughts

Take heart and stay feisty,

If you’ve found something that speaks to you here

Please share it, restack it, or forward to a friend. This letter is this editor's off-hours labor of love. Your word of recommendation is how our kindred community grows.

Your insight + Maggie's breaking the rules = I just purchased my hardcopy!

You Could Make This Beautiful is my mother's day present to myself.

🌷🌷🌷🌷

As a reader, I absolutely adored Smith’s choices. I couldn’t stop turning the page. As a writer, witnessing another writer (poet) write like this and so effectively felt freeing and inspiring.